Overview

Location

The archaeological site of Khirbat ‘Ataruz is located on the ridge of Jabal Hamidah in central Jordan, nestled between the Wadi Zarqa Main to the north and the Sayl Haydan to the south. This historic ruin lies near the modern town of Jabal Hamidah, approximately 10 kilometers west of Libb and 3 kilometers east of the Hellenistic and Roman ruins at Machaerus.

Research Background

The vicinity of Khirbat ‘Ataruz was first surveyed by Schottroff in 1966, revealing it to be one of the few permanently settled sites from the Iron Age within the Jabal Hamidah region. This initial survey highlighted the site's significance in understanding the area's ancient habitation patterns. Later, in 1985, Niemann conducted further examinations at the site, uncovering Iron Age pottery and a fragment of a terracotta figurine, adding to its archaeological importance. Despite these earlier investigations, much of the ‘Ataruz region remains largely unexplored for its archaeological potential. Notably, no systematic excavations had previously been explicitly conducted at Khirbat ‘Ataruz, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of its historical and cultural context.

The La Sierra University team has shown sustained interest in Khirbat ‘Ataruz and its surrounding areas for archaeological research since 1996 when Chang-Ho Ji launched the Dhiban Plateau Survey Project. Given that the Ataruz area lies just north of the survey region across the Sayl Haydan, the geographical and archaeological connections between the Dhiban and Ataruz areas were evident. These close ties underscored the importance of studying the two regions in tandem to gain a comprehensive understanding of the occupational history of central Jordan.

In 1998, as part of an extension to the Dhiban Plateau Survey Project, Chang-Ho Ji conducted a brief reconnaissance surface survey at Khirbat ‘Ataruz. This preliminary exploration yielded a diverse collection of pottery spanning multiple periods, including the Iron Age, Hellenistic, Roman, and Islamic eras. Several ancient wall lines on the site's acropolis were particularly interesting, clearly visible and traceable above ground. These findings highlighted the rich archaeological potential of Khirbat ‘Ataruz for studying the Iron Age, classical periods, and Islamic history. Additionally, the ceramic evidence recovered from Khirbat ‘Ataruz was broadly consistent in shape and style with pottery from other Iron Age, Hellenistic, Roman, and Islamic sites in the Dhiban Plateau. This compatibility further emphasized the two regions' interconnected historical and cultural significance, solidifying their joint study's importance.

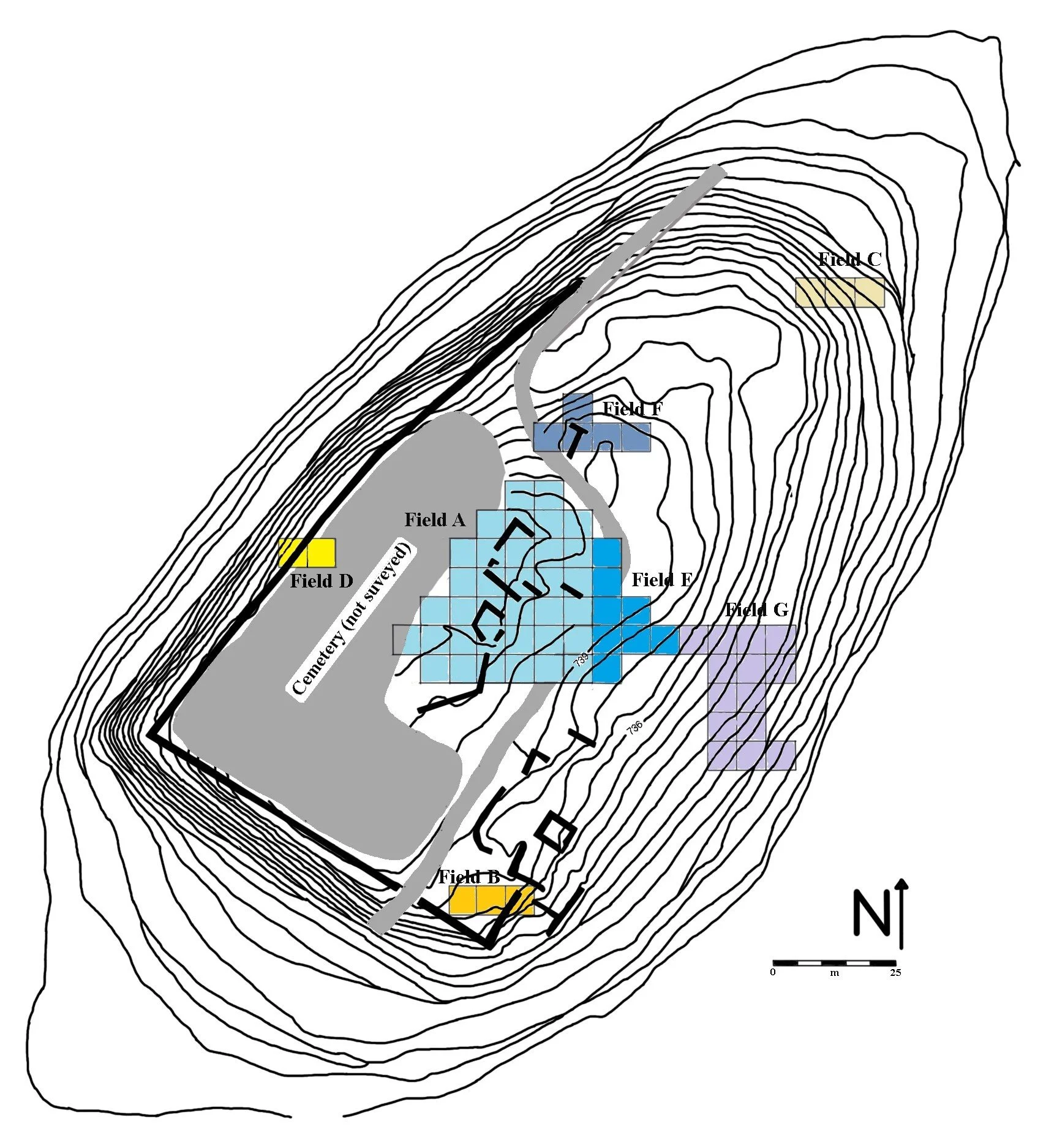

In 2000, Chang-Ho Ji and his project team initiated excavations at Khirbat ‘Ataruz by opening two 6 m x 6 m squares in the acropolis area. The objective was to establish a preliminary stratigraphy to guide future large-scale excavations. Over the following years, from 2000 to 2024, 15 excavation seasons were conducted under the auspices of the ‘Ataruz Regional Research Project, focusing on six key areas: the acropolis (Fields A and E), the southern defense wall (Field B), the northeastern slope (Field C), the western gate system (Field D), the eastern hill (Field F), and the southeastern slope (Field G). The project expanded significantly during this time, evolving into a consortium involving multiple institutions. The current collaboration includes La Sierra University (Chang-Ho Ji), Brigham Young University (Aaron Schade), Sahmyook University (Choong Ryul Lee), and Andrews University (Robert Bates). This consortium has played a vital role in advancing the excavation and research efforts at Khirbat ‘Ataruz.

Historical Context

‘Ataruz is mentioned in biblical and historical sources and has been identified with the ancient city of Ataroth. It appears several times in the Bible, including Numbers 34:32, which states: “The children of Gad built Dibon, Ataroth, and Aroer...” The Bible also notes that the tribe of Gad was assigned territory in Transjordan, and Ataroth was built as part of their settlements.

‘Ataruz is further referenced in the Moabite Stele. According to this inscription, the Gadites had lived around Ataroth from ancient times, and King Omri of Israel had built a city and a cult center in the region. As the power of the Omride dynasty began to decline, Mesha, the king of Moab, seized the chance to “throw off the yoke” of the house of Omri and unify the area under his rule. He launched a campaign against Ataroth, where he killed its inhabitants as an offering to his god, Chemosh. He destroyed the temple and removed its sacred object, referred to as the “ariel of David,” transporting it to Qarioth—likely a city near ‘Ataruz—where he set it up as a memorial of his victory. Mesha subsequently repopulated Ataroth with two groups called the Sharonites and the Maharatites, although their precise identities remain unknown.

Settlement History

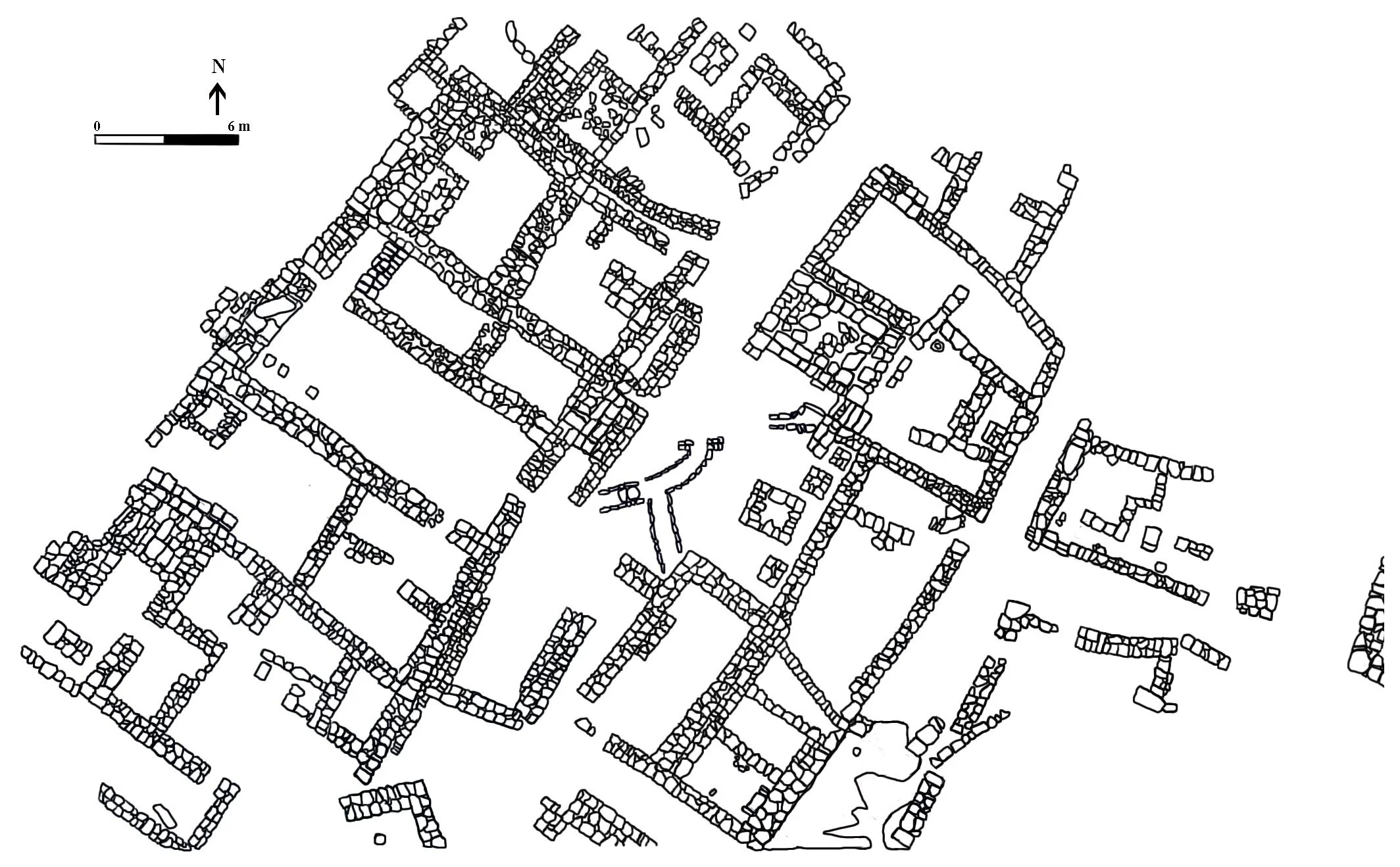

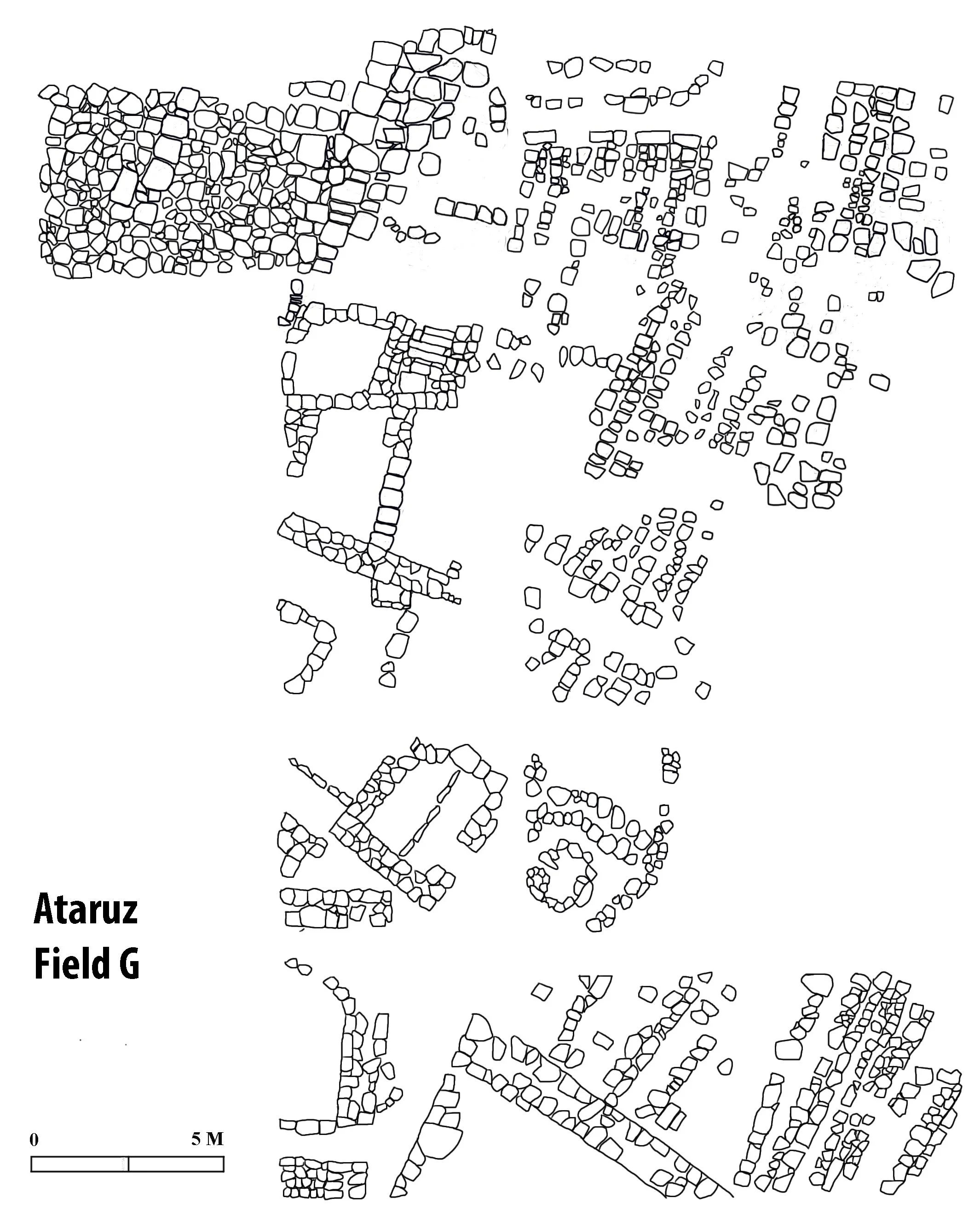

The archaeological remains associated with the temple at Khirbat ‘Ataruz indicate at least two distinct phases of cultic activity during the late Iron IIA period (ca. the late 10th to early 8th centuries BCE). The site was a major cultic center, likely constructed and sustained by national or regional power. Strategically positioned at the site's highest point, the temple complex reflected careful planning and a central location that underscored its importance. A standing stone beside the offering table represented the principal deity within the Main Sanctuary. Further evidence suggests that a bull motif also symbolized this god. The city itself was fortified by double- or triple-layer defense walls, and a monumental staircase on the eastern slope connected the east city gate directly to the temple atop the acropolis, ensuring convenient access for visitors and worshipers.

This Iron IIA temple ended violently in the late 9th century BCE, after which the area was sealed and abandoned. However, the site was rebuilt and continuously used during the Iron IIB–IIC periods. Cultic activity persisted into the early 8th century BCE, marked by the construction of a small Moabite sanctuary on the eastern side of the acropolis. The adjacent eastern space was utilized explicitly for rituals associated with this sanctuary. This phase of cultic use came to an end in the early 8th century BCE. In the following Iron IIB and early Iron IIC periods (8th–7th centuries BCE), the site transitioned to primarily domestic and residential use, as evidenced by discoveries of kitchen remains, storage facilities, and water channels. By the early Iron IIC period, the site appears to have been entirely abandoned, likely no later than the early 7th century BCE.

The Hellenistic occupants of the tell reused earlier Iron II structures, incorporating two long walls into the Hearth and Double Platform Rooms. In the southwestern part of Field A, several walls and rooms were constructed during the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods (ca. 200 BCE–100 CE). An Iron Age room in Field E was also repurposed during the late Hellenistic period, yielding a complete lamp dated to the 1st century BCE. In Field C, excavations along the northern side of Khirbat ‘Ataruz uncovered late Hellenistic–early Roman structures, including bath installations with plastered steps and walls. The discovery of numerous storage jar sherds suggests that ‘Ataruz was actively involved in cereal farming and the production of oil or wine. Furthermore, evidence indicates that the caves on the northern foothill of the site were used for residential and industrial purposes during the early Roman period. By the end of the 1st century CE, agricultural decline and escalating political instability in the region led to the site's abandonment.

Khirbat ‘Ataruz remained unoccupied for nearly 600 years before a brief, small-scale resettlement in the Early Islamic period (ca. 7th–8th centuries CE), evidenced by two wall lines in Field A that may date to this time—though the data are minimal. The site was fully reoccupied during the Mid-Islamic period (late 13th–early 15th centuries CE) when it was reestablished as a medium-sized village. However, its exact size and layout remain unclear. Many of the walls and buildings dating to this period were constructed by reusing earlier structures rather than erecting entirely new ones. Notably, much of the building stone from the early-to-mid Iron IIA temple complex was dismantled and repurposed, particularly in Fields A and G. Despite this reliance on earlier materials, there is no doubt that Ataruz flourished as a populous and thriving village during the Mid-Islamic period.

Maps

Location of Khirbat 'Ataruz

Contour Map of 'Ataruz with Excavated Fields (2024)

Architectural Remains of the Iron Age IIA Temple at 'Ataruz, Fields a & e (2024)

Monumental staircase and Architectural remains on the eastern slope, Field G (2024)

Staff

-

Chang-Ho Ji, Ph.D.

Director, Khirbat Ataruz Project

Center for Near Eastern Archaeology

La Sierra University, CA

cji@lasierra.edu -

Aaron Schade, Ph.D.

Co-Director, Khirbat Ataruz Project

Dept. of Ancient Near Eastern Studies

Brigham Young University, UT

aaron_schade@byu.edu -

Choong-Ryeol Lee, Ph.D.

Associate Director, Field Supervisor

Graduate School of Theology

Sahmyook University, Seoul, Korea

sevenlee94@hotmail.com -

Robert Bates, Ph.D.

Associate Director, Field Supervisor

Institute of Archaeology

Andrews University, MI

bates@andrews.edu -

John McBride, Ph.D

Geologist, GPR Project Director

Geological Sciences

Brigham Young University, UT

john_mcbride@byu.edu -

Lawrence T. Geraty, Ph.D.

Senior Project Adviser

Center for Near Eastern Archaeology

La Sierra University, CA

lgeraty@lasierra.edu -

Christopher Rollston, Ph.D.

Project Paleographer

Dept. of Classical and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations

The George Washington University, Washington DC

rollston@gwu.edu

Consortium Institutions